Going Beyond SEL: Another way to look at how we can help our students accelerate recovery

Social Emotional Learning (SEL) is the new buzz word used by every pundit and publisher these days. As special

educators, we have always addressed essential social skills based on each child’s individual needs. Though it is

wonderful that SEL is getting so much attention, and funding, it is critical to clearly define how to address SEL

within the context of maintaining compliance with Individual Education Plans (IEPs). One size does not fit all. This

blog post challenges readers to explore a continuum of developmentally appropriate social skills, as they build

IEP plans based on students’ needs vs a publishers’ catalog.

Going Beyond SEL: Another way to look at how we can help our students accelerate recovery

By Joyce Whitby

April 2022

The abrupt shutdown of life as we knew it, just a little over two years ago, has taken its toll on so many aspects of everyday life. Our whole learning ecosystem – public, private, K12, higher education, virtual – has been shaken not stirred!

As educators, we cannot afford to wait in order to build a thorough recovery plan that meets the unique needs of our very diverse learning population. The impetus now is to accelerate recovery, help learners master unfinished learning, and get them back on a “normal” trajectory for completing their education. Clearly the full impact and long-term implications are still being examined, and will be for years to come, but since we don’t have ability to time travel into the future and analyze that research, we need to build our recovery model now sans hard data.

Miraculously, the US Department of Education (US ED) immediately projected and recognized the overwhelming needs that would be forthcoming, and has instituted several layers of funding in waves of significant funding under CARES, CRRSSA and ARP*. What is truly significant with these funding guidelines, is that they specifically call out both a need to target “academic learning loss and social emotional learning”. There really has never been a time where mental health, and social emotional well being were as put on par with academics.

Though this is a most welcomed departure from the norm, it does open up a host of questions and even controversy around the areas of emotional wellbeing, which leaves with critical questions:

- “What is SEL?”

- “What isn’t SEL?”

- “Who needs SEL? When? How often? Delivered by whom?”

- “How do we measure the effectiveness of SEL?”

We are so anxious to get back to “normal”, that school leaders are jumping into this area feet first, regardless of the ambiguity around what SEL is, and what it is not. Hence the public outcry, from parents, and concerned community members, from politicians and the media has grown exponentially. Much of which is based on misinformation and lack of facts about what is included when we address the concept of SEL and how.

Long before the pandemic, in fact since 1994, The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL https://casel.org/) has been the de facto standard for explaining SEL via a framework commonly known as the “CASEL wheel.” At the center are five core social and emotional competencies, which are broad, interrelated areas that support learning and development. Circling them are four key settings where students live and grow. School-family-community partnerships coordinate SEL practices and establish equitable learning environments across all of these contexts.

the de facto standard for explaining SEL via a framework commonly known as the “CASEL wheel.” At the center are five core social and emotional competencies, which are broad, interrelated areas that support learning and development. Circling them are four key settings where students live and grow. School-family-community partnerships coordinate SEL practices and establish equitable learning environments across all of these contexts.

Frankly, just diving into the research-based CASEL framework in isolation misses what we, as special educators, know is essential for students who are not performing at age-appropriate levels. That missing component is simple to base instruction on an individual’s needs. The “one size does not fit all” rule applies to everything we do in special education, so let’s look at how this should drive our approach to ensuring essential social emotional wellbeing is addressed appropriately. What we are missing as a whole in education is that we suddenly have a huge wave of students who were not previously classified with “special needs”, who now exhibit a host of issues that impede their ability to learn. No, we don’t need to classify each and every student, we need to intervene. Most of what we are seeing in the classroom of 2022 can be remediated, retaught, replenished, and restored.

If we peel back the fancy pedagogical language, the situation is a bit easier to understand. We have students across all grade levels, who have missed out on real time social interactions for two years. The importance of those interactions on the development of the whole child is greater than anyone ever imagined. Suddenly those students are back in a full-time classroom, after two years in an array of settings. It’s no wonder that they are demonstrating inappropriate behaviors. Students are breaking down in tears, or lashing out in frustration, as they encounter situations for which they are just not prepared to handle. Here are a few to consider:

- Second graders don’t know the basics – how to line up, raise their hands to ask a question, or how to take turns. These are things that they would have learned and practiced in Kindergarten and 1st grade.

- Middle schoolers that haven’t been around their peers for two years, are shocked to find that their friends are no longer little children, but rather, they are developing adolescents, with a host of complex social mores.

- High School juniors and seniors are overwhelmed with tight timelines to comply with graduation requirements and college applications, even though they feel they just started High School.

The plot thickens as we consider teachers who have given every ounce of their being to helping students survive during remote and hybrid instruction. Those educators are also in need of respite, yet what they are encountering is a call to action to raise the bar even higher.

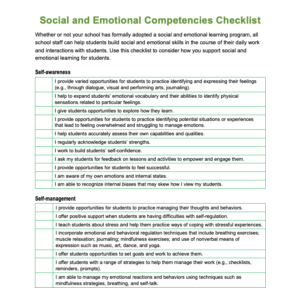

Given this reality, it is clear that everyone is dancing as fast as they can. Perhaps now is the right time to reset expectations, and address reasonable goals based on individual needs. Perhaps now is a great time to meet students where they are, and guide them along the path to pick up skills they missed. A great checklist of developmentally appropriate social skills and emotional competencies is available at Trauma-Sensitive Schools. Social and emotional competencies, such as self-regulation, strong coping and problem-solving skills, and positive social  connections, buffer the effects of trauma and strengthen resilience. As we examine a student’s ability to manage themselves in socially appropriate ways, we can see areas that need direct instruction in social skills, coping skills, and life skills.

connections, buffer the effects of trauma and strengthen resilience. As we examine a student’s ability to manage themselves in socially appropriate ways, we can see areas that need direct instruction in social skills, coping skills, and life skills.

A tried-and-true mantra in Special Education is “teach to a student’s strengths to strengthen their weaknesses.” This is a great guiding principle for us to follow in terms of helping students during this time of recovery. All teaching practices should be appropriate to children’s ages and developmental status, attuned to each of them as unique individuals, and be responsive to the social and cultural contexts in which they live.

References

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (n.d.). CASEL (website). Retrieved from http://www.casel.org/

Developmentally appropriate social skills and emotional competencies checklist. Trauma-Sensitive Schools Training Package. https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/TSS_Building_Handout_7_social_and_emotional_competencies.pdf

*Maximizing ESSER Funds in the American Rescue Plan Act to Prioritize Social Emotional Learning. Whitby, Joyce. Brighten Learning (website). https://socialexpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Maximizing-ESSER-Funds-to-Prioritize-Social-Emotional-Learning_2022.pdf